Everything I’ve learned about holding algorithmic power to account

May 10th, 2023 – Claudio Agosti

October 11th update: a new spin-off from the Tracking Exposed experience: the Reverse Engineering Task Force.

The Tracking Exposed Adventure

Step 1: Build free-software to investigate the platforms

Step 2: Build the community of researchers

The surprising Pornhub experiment

Training the next generation of researchers

Step 3: Litigate against the platforms

Step 4: Build better alternatives

Step 5: Expose platforms through high profile press

1. The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house ~ Audre Lorde

2. Building is hard - do it together (please)

4. High profile press scrutiny works

5. Focus and leverage expertise

6. We have world class technology and team of expert algorithm auditors

The Changing Landscape of Algorithmic Accountability

2. The algorithmic accountability field has expanded

3. Regulation is getting there

6. Alternative platforms increased uptake

Foreword

After 7 years of analyzing, exposing and holding algorithmic power to account the Tracking Exposed collective ended at the beginning of 2023, and completed the transition towards its new chapter, AI Forensics, in May 2023.

For the team behind Tracking Exposed, this is both sad and exciting. It’s sad because our collective has achieved incredible things together, but we’re closing Tracking Exposed in order to make way for a new chapter of our work on exposing and holding algorithmic power to account, which is, in fact, very exciting.

Clearly there is still much work to do in this field, but since we started Tracking Exposed in 2016 the landscape has changed. We learned a lot about where and how to focus, and the most effective way to conduct research and build tools for real world impact.

As its founder, I want to celebrate what the Tracking Exposed team achieved together, and what we learned in the process. I hope sharing our story motivates more people to join the ecosystem of actors working in the important fields of digital rights and examining algorithmic power.

The Tracking Exposed Adventure

Cast your mind back to 2015…

In 2015 Shoshana Zuboff had not yet written The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. Data collection without consent was rife everywhere online. Mastodon was still just an extinct elephant. Monopolistic tech platforms built with a Silicon Valley ideology such as Facebook, Instagram and Twitter had dominated our lives, mostly uncritically, for the best part of a decade. Cambridge Analytica’s now infamous infrastructure was being quietly deployed in the British Brexit debate, but the consequences on western political events were yet to unfold. Privacy activists’ concerns were downed out by the novelty and utility of these new ways of communicating, with many people believing that the truly dystopian outcomes could only happen in totalitarian regimes. We didn’t have robust language to even describe the problem, let alone change it.

When I first became a privacy activist in 2000, my main concern was government surveillance. However, over time, corporate influence has grown significantly, and it was time to take action. Despite high-quality, high-profile reporting, such as in the case of Cambridge Analytica, we have seen many instances of algorithmic manipulation go unpunished. By the summer of 2016, I could no longer wait for platforms to fix themselves or for regulators to take action. Without systemic change, Big Tech's undue and unaccountable influence on democracy would continue. So, I had to act.

The Vision

Tracking Exposed started as a free software analysis tool meant for activists and researchers working to expose the digital tracking and online profiling that was invisible, inescapable and unaccountable. I believed that algorithms were social policies and therefore should be subject to public scrutiny.

I hypothesized that if we could see the true extent of the problem then we could make better choices about our online lives, and regulators would be better informed about the reality of profiling and algorithmic manipulation online and therefore able to make better laws to stop it. I dreamed of a future where our data was unlocked, and we had the freedom to take it to more ethical platforms - and in doing so end the monopoly of big tech.

We didn’t have a lot of money, but we made up for it with passion and principles:

- Platforms cannot be trusted to “mark their own homework”. We needed independent data access, free from obfuscation

- Collaborate, don’t duplicate. With little money against multi billion dollar companies we set out to share resources and expertise with others alongside us.

- Don’t replicate systems of power we’re trying to deconstruct. We wanted to create an organization that lived its power-sharing values through non-hierarchical governance.

- Imagine alternatives. We believed it was necessary to create visions of viable alternatives to the existing platforms, not just critique or change the current ones.

- Knowledge is freedom. We believed that empowering people with the knowledge of how they were being tracked and why this is problematic would lead to a people-powered movement for systemic change.

Step 1: Build free-software to investigate the platforms

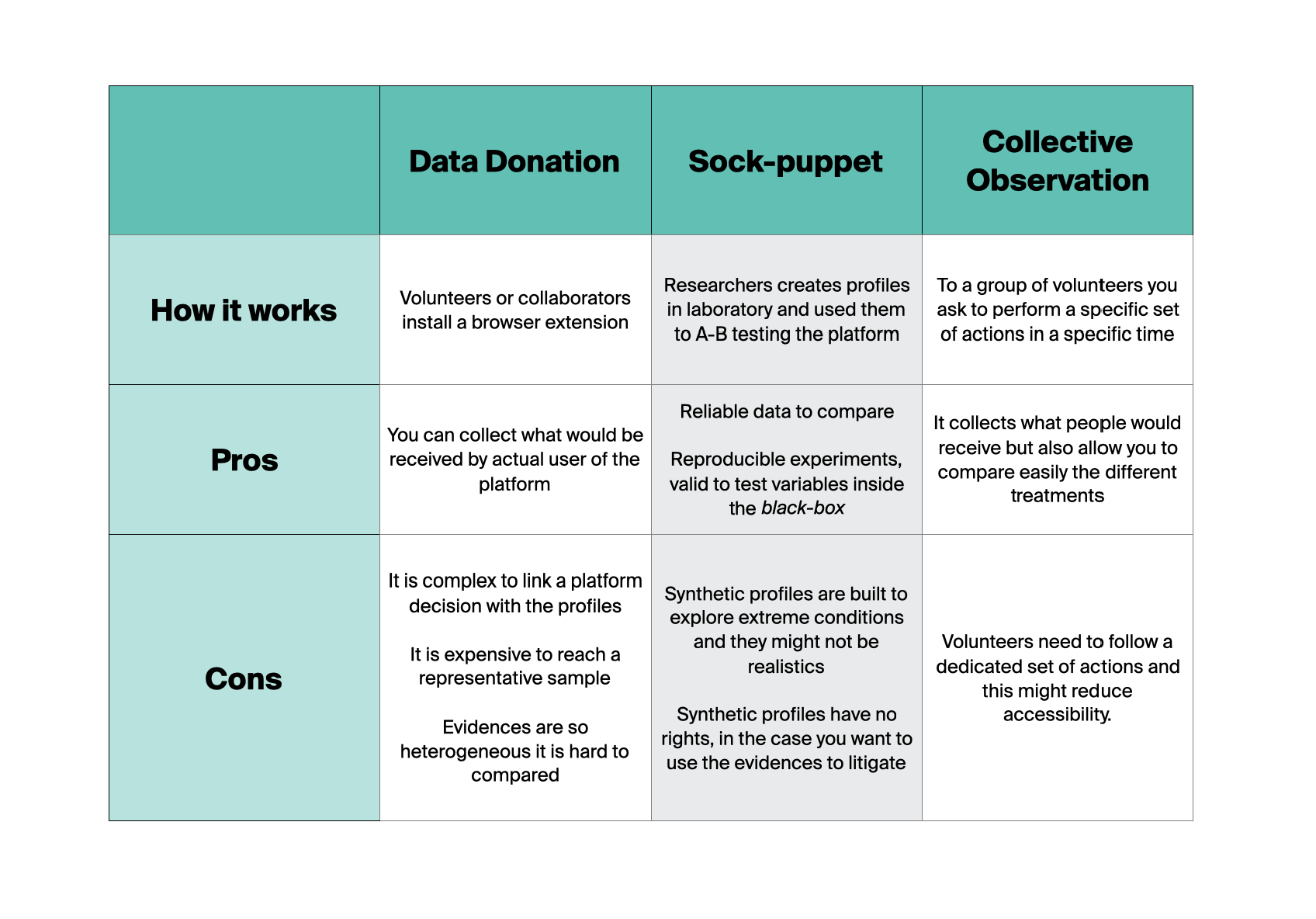

We set out to make the biggest tech platforms’ behaviors visible by developing scraping technology that showed exactly how tech platforms were making decisions about content at scale. We supplemented this information with Data Donation (asking users to collect data via a browser extension that linked their online activities to the content shown by the platforms, for us to analyze) and sockpuppeting (collecting the same data manually via multiple testing profiles). Combined, we call data donation, scraping and sockpuppeting Collective Observation.

We released our tools as free software, it was flexible enough to be used for all the three methodologies expressed. Free software is like open source software, but imbued with additional anticapitalist principles. We wanted everyone to be able to see how invisible algorithms inside Facebook were shaping our reality.

It worked. For the first time, it was possible to compare what Facebook was doing between countries, between different user profiles and between users with different behaviors.

Profiling and politics: the early experiments

We started with Facebook, as the biggest and most problematic platform, and focused on elections and political issues. What news was being shown to us on big platforms, and what implications did that forced information diet have on our wider political systems?

Our early experiments showed the power and the limitations of the scraping, data donation and sockpuppet approaches. We were able to get information that showed how Facebook’s algorithmic content decisions were shaping our information diet in the 2017 French Election, The Argentinian G20 the same year, and the Italian 2018 election too (Privacy International wrote about the findings).

One shocking discovery that had only been suspected until we found the evidence, is the existence of a list that Facebook created to determine what was credible news. In one investigation we found that center-left newspaper La Repubblica was inserted into users’ feeds, regardless of their political leanings or platform behavior.

This was confirmed years later in the 2021 book “An Ugly Truth: Inside Facebook's Battle for Domination” – By Sheera Frenkel and Cecilia Kang:

The day after the election, the team held a virtual meeting with Zuckerberg in which it requested he approve new break-glass emergency measures. These included an emergency change to the News Feed algorithm, which would put more emphasis on the "news ecosystem quality" scores, or NEQS. This was a secret internal ranking Facebook assigned to news publishers based on signals about the quality of their journalism. [...]

Under the change, Facebook would tweak its algorithms so people saw more content from the higher-scoring news outlets than from those that promoted false news or conspiracies about the election results. Zuckerberg approved the change.

It was as we suspected: Facebook had created what they called the News Ecosystem Quality (NEQ) list, and - without declaring that they were doing this - used it to shape political discourse in countries around the world.

Though this particular investigation didn’t pick up traction at the time, we were starting to get noticed for other work. The World Wide Web Foundation published our first report, showing amongst other things that Facebook was showing more news about homicides than femicides.

Everywhere we looked we found issues, but our research was limited by how many people we could persuade to download our browser extension, how many sock puppet accounts we could set up and manage without losing our minds, and by the type of data we could collect via scraping.

Expanding our scrutiny beyond Facebook

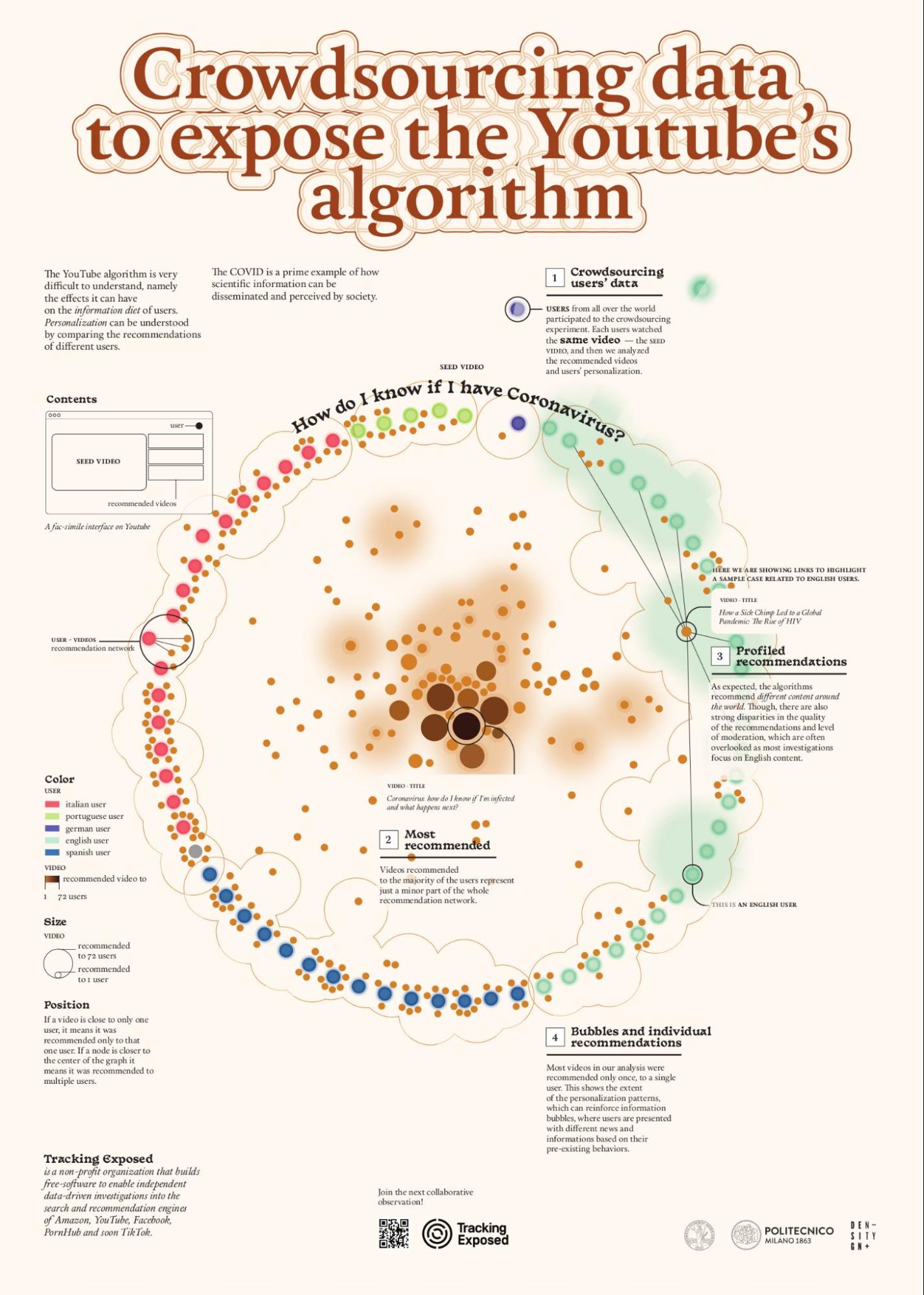

We knew we needed something bigger for the scale of the issue we were fighting. We also felt an urgent call to look at the algorithms of other platforms beyond Facebook. As our contributors grew we also built scrapers and data donation browser extensions for YouTube, Pornhub and Amazon. With every new platform we investigated, we found more evidence of the effect of algorithms on society.

Experimenting with a dozen students, we visualized the amount of common recommendations (left image below) when the browser has no personalisation, and the amount of personalisation there is when the platform has had a chance to study your behavior (right image below). We also played with this concept by testing whether this also happens with searches, how quickly youtube starts profiling you, and whether political content is treated differently. We were the first to release an extension for analyzing the youtube algorithm to enable researchers who wanted to study it. Several groups of students are working with us on the investigations in 2019, 2020, and 2021.

We also found that even though YouTube had provided an API where they report recommendations, it did not show the full picture. Our methodology showed what YouTube was actually doing via personalisation algorithms by collecting the videos recommended by Youtube on the user interface. We have discovered that only a small amount of recommendations between API and scraping were actually the same.

We became even more ambitious after each new investigation on each platform. Our work had unequivocally shown that:

- Personalised algorithms were everywhere, and profiling and involuntary data collection was rife

- Algorithmic manipulation was not being explained to us

- Political content was being treated differently to non political content (with important implications for the very concept of democracy)

- Official APIs were unreliable as a source of information about how platforms’ algorithms work.

However, it was clear that our discoveries wouldn’t change the business model of data exploitation or Facebook's power over society. We needed even more researchers to expose the vastness of the issues, and to move beyond just exposing the problem and work towards a solution.

In these first two years our collective was mostly volunteers, but we were also grateful for small grants from World Wide Web Foundation, Lush via the KeepItOn campaign, the Shuttleworth Foundation flash grant, and the Data Transparency Lab prize. These small grants didn't allow yet for long-term planning, but at least allowed me to pay my bills and occasional external experts. An Italian Open data company, Open Sensors Data, was the very first sponsor, providing valuable skills rather than funds.

Step 2: Build the community of researchers

I decided to double down on the collective’s unique skill set and network - technology and academic research - and build more robust Collective Observation tools for the research community. This was a bet on our collective power. If we could engage the whole emerging field of algorithmic accountability maybe we could stop the omnipresent algorithms of Big Tech.

I became a research associate at the University of Amsterdam, under the guidance of Principal Investigator Stefania Milan in charge of ERC DATACTIVE. Together with a post doctorate, Davide Beraldo, we devised a methodology to make more replicable algorithmic analysis.

Algorithms Exposed

In 2018, we won a substantial European Research Council grant for this work, and it opened up a new era for Tracking Exposed where we could plan 18 months ahead. Finally we could build and pay a team. The goal was to turn our methodology into a product that researchers could use, to train researchers in how to investigate unaccountable algorithms, and to develop research to further the field. We called this project Algorithms Exposed.

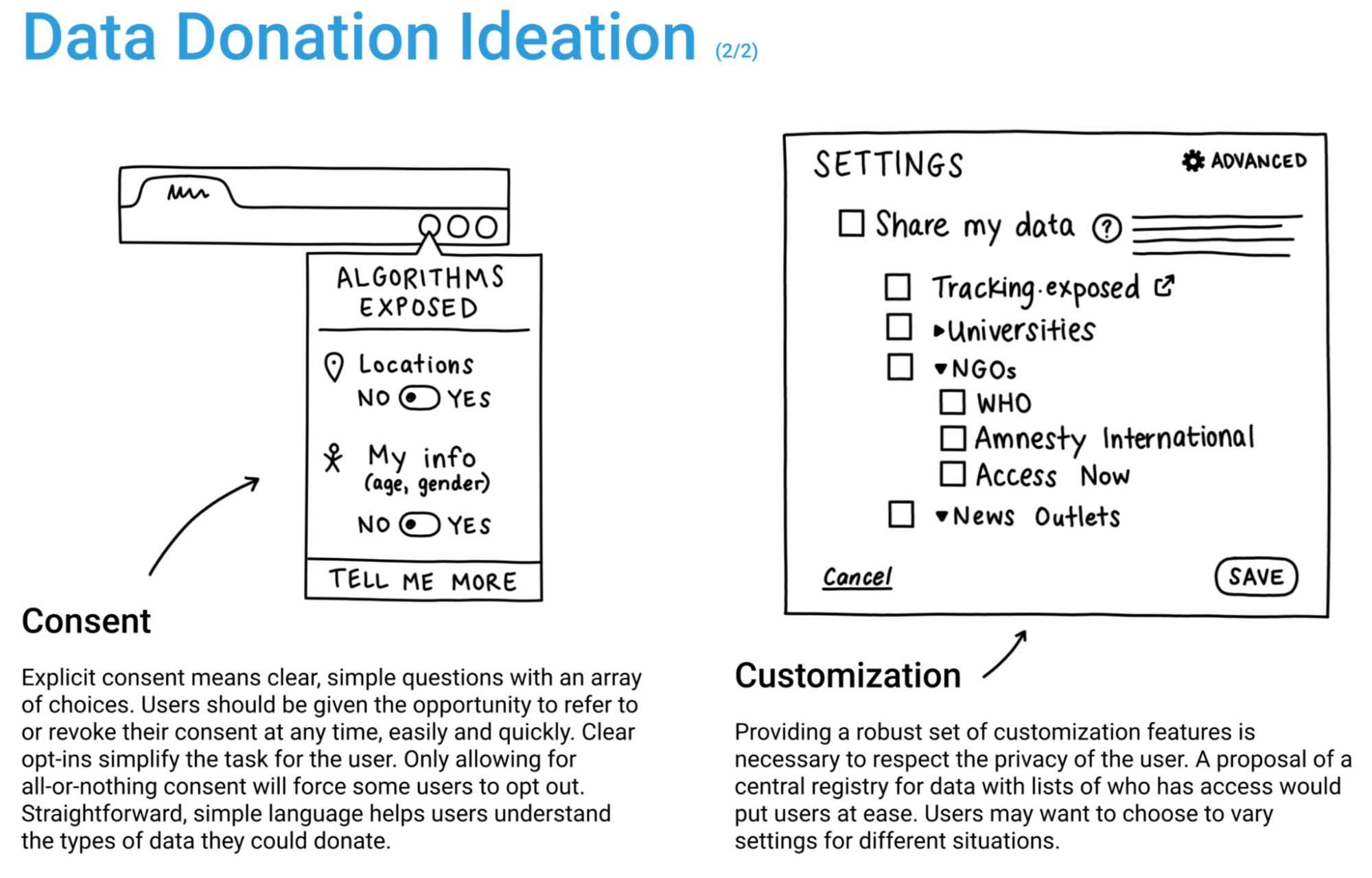

We hired SimplySecure (later rebranded in SuperBloom) to run a workshop on data donation Feb 2020. The report shows how our thinking shaped the best practice in the field, and the process we went through to determine what good data donation looks like. Interestingly, a few months after our collaboration Simply Secure did consultancy work on the design of Data Donations for CitizenBrowser, TheMarkup's equivalent product. Our work helped to popularize the concept, and The Markup’s adoption of our methodology began to legitimize our Data Donation approach - data donation, scraping and sockpuppeting - as a new way of exposing how algorithms actually work.

During this time we - and particularly with the arrival of our Head of Research Salvatore Romano - pioneered even more new methodologies for algorithm analysis, and investigated the algorithms involved in:

- Is the Amazon profiling algorithm violating the GDPR? (video investigation, in italian).

- Product recommendation and gender discrimination on Amazon.

- How Youtube quickly profiles you and personalizes search results.

- A massive data donation in the Netherlands, on how to verify Facebook political transparency.

- Covid disinformation on YouTube.

- The world according to Tiktok: mapping digital boundaries and algorithmic proximities.

- The datathon, organized by Berlin Data Science for Social Good, where 20 researchers play with the Data Donation dataset of Facebook.

Below is an infographic designed by Beatrice Gobbo, explaining a portion of all the insights gathered in our collaborative observation made on Covid and YouTube.

The most interesting part of Algorithms Exposed was teaching during the Winter and Summer schools of the Digital Method Initiative, a concept created by Richard Rogers to support social scientists studying platforms. In the final Winter School before Covid a group of 30 students used Algorithms Exposed to explore 5 different ways to map the discrimination and personalization that happens on Amazon. We wanted to understand how dynamic pricing works, if this is actually a result of your spending ability, and study how third-party sites inform Amazon about your purchasing power. One of the students also produced his master's thesis on using amazon.tracking.exposed to gather evidence of GDPR violations.

The surprising Pornhub experiment

At Winter School 2019 I met Giulia Corona, at the time a student at the Politecnico di Milano, who wanted to do a thesis talking about the Pornhub algorithm. Although I was initially intending to investigate other platforms, I was thrilled to support Giulia. Also, the evidence collection mechanism was easier to make than social media platforms, and so one month after our meeting, pornhub.tracking.exposed was already out there!

It was particularly exciting to talk about algorithms beyond the usual platforms we investigate. I still remember a prominent European politician asking during a call: “I understand the research on Facebook and Youtube, but why Pornhub? Those are the kind of personalization you might like!”. It is a form of unscrutinized power that has a huge impact on people's sexualities, identities and our social fabric.

We organized the first Collective Observation (also known as “Collaborative Observation”), with an announce on Reddit inviting Redditors to follow a sequence of predetermined actions. Around a hundred participants watched porn for science, and the collected evidence was enough for us to start to understand how Pornhub recommendations work. Later on, through this data, we have identified the difference between Pornhub and Youtube’s content recommendation approach. This project also allowed us to reflect on how the algorithm behind the monopoly of pornography also influences the perception of sexuality itself. Together with several academics, mainly from the university of Milan, we published The Platformization of Gender and Sexual Identities: An Algorithmic Analysis of Pornhub in PornStudies.

Then in 2021, a freshly certified lawyer Alessandro Polidoro approached our group, and we included him in the framing of Pornhub's profiling as a violation of Article 22 of the GDPR. One of the highest victories of Tracking Exposed could have been that the algorithm analysis would be used to prove data processing violations. For this goal we set up a years-long legal strategy, and the action is still ongoing.

Now that Tracking Exposed closes, the advocacy and the legal actions are brought forward by the StopDataPorn campaign.

Training the next generation of researchers

Since 2019 we have run these week-long researcher training programs twice a year, and in total have trained around 250 researchers in the methodologies we developed. These researchers have gone onto careers in algorithmic accountability, producing at least 20 articles, and 11 academic papers that we know about. I’m very proud that we trained a generation of researchers and I’m sure their impact on the industry will be felt for years to come.

Our skepticism of the official platform APIs proved to be useful. We consistently found that other research institutes that used data provided by companies end up analyzing the interactions between people and the content they produce and interact with. But this is a way to study people, and not platforms.

In these study groups we were able to distinguish research aimed at the platform vs the analysis of the content in the platform (which is the responsibility of the community and the guideline enforcement). This work was critical to define and separate the numerous research areas in algorithmic accountability - for example the difference between content policy, governance and algorithmic manipulation, which are now considered their own distinct fields.

Makhno

To address the need we discovered for researcher tools that highlight and investigate content takedowns on powerful platforms, in 2022 we teamed up with Hermes Center for Transparency and Digital Human Rights to create Makhno.

Funded by Mozilla Foundation, Makhno is a tool that lets anyone - from creators whose livelihood is at stake from unaccountable content takedowns to researchers investigating human rights issues - to flag content policy takedowns. Platforms have rules and regulations that dictate what will and won’t be allowed on their platforms. However, sometimes the reasons content is taken down are not so explicit and in other instances it happens under nefarious circumstances.

Makhno is an important and powerful tool with a lot of promise, it uses the Tracking Exposed scraping experience to verify if a content is present or not, allowing us to do a map of geoblocking on the main platforms. Future development will be stewarded by the Hermes Center for Transparency and Digital Human Rights after Tracking Exposed closes.

Step 3: Litigate against the platforms

By 2019 we had an overwhelming amount of evidence of nefarious platform behavior from our own research and that of the community of researchers we’d been building.

We couldn’t publish the research fast enough, and it wasn’t changing platform behavior even when we did. We felt that rather than just do more research we should also try strategic litigation as a way of bringing high profile, international attention to a small number of the vast problems we saw when we run platform scrutiny. We had gathered many examples of GDPR violations, and started to construct cases against the platforms so they had to answer for their behavior in the court of law, not just public opinion.

We had strong cases against two large platforms, and even won significant funding from Digital Freedom Fund to litigate. But after 2 years of actions this path has proved inconclusive.

The pace of the violations and the pace of the litigation process are completely incompatible. We could find evidence easily, but by the time we documented it for litigation it had changed; to be replaced by a new violation. A ghoulish game of whack-a-mole where the mole always wins.

This is one of the reasons our new initiative, AI Forensics, won’t pursue litigation. It’s important work but we have found much higher impact with releasing the findings to the court of public opinion immediately, as we did with our scrutiny of TikTok’s actions in Russia after the Ukraine war (see step 5).

Riders and the gig-economy

Algorithm analysis has become famous for the impact of social media on society, but the problem is much more pervasive. I thought it would be strategic to explore other narratives to understand why society should take control of its algorithms. Risky and precarious jobs are also usually performed by people usually at the margins of society. To counter the risk of exploitation of vulnerable segments of society, it is important to ensure transparency and accountability of automated decisions on gig economy platforms.

It is harder to investigate these platforms because they work on mobile devices. It is not possible to perform a sock-puppet audit. Hypotheses in this context are harder to be tested. However, since the very beginning of Tracking Exposed, Gaetano Priori, a mobile security analyst also close to the Riders struggle in Turin, was ready to test something entirely different

In 2019, with the support of Attorney Stefano Rossetti, we built a questionnaire to survey the riders, hoping this would give us their perspective on what are the violations faced, hence where to investigate. I developed a partnership with IRPI media, an Italian investigative media outlet working on the project Life Is a Game and Rosita Rijtano, authoress of “Insubordinati, Inchiesta sui riders” in order to recruit riders to fill in the questionnaire - which has been crucial to our reverse engineering activities.

Meanwhile, relations with the European Trade Union Institute (ETUI) are progressing and a paper will soon be published on how workers' unions can use reverse engineering and the GDPR to protect the rights of intermediary workers.

October 11th Update, the report is public: Exercising workers’ rights in algorithmic management systems.

I hope this set of experiences can really inform the labor unions on how the power dynamics affect the digitally mediated work. This path somehow resembles the true nature of Tracking Exposed approach: suspect, explore, see, engage, collaborate, produce.

October 11th Update: This effort has been encapsulated in a new Tracking Exposed spin-off, focused on supporting unions that expose surveillance and discrimination against platform workers. It is an informal group built upon the experiences of this chapter, and we have named it the Reverse Engineering Task Force.

Step 4: Build better alternatives

By this time we very clearly knew the problems, and we had hard-won evidence it was extremely challenging to change platform behavior with research and litigation alone. We decided to try a new approach, which had always been core to my thesis on how to stop invisible, unaccountable algorithms: creating alternative platforms.

Around this time Marc Faddoul joined Tracking Exposed. Marc started his career as an algorithm designer but soon he became passionate about the impact these systems had on society. He pursued this interest at UC Berkeley, where he conducted research on YouTube's recommender system. We shared the same vision that in order to free users from exploitative recommender systems, adversarial methods were needed both to provide independent scrutiny and to offer alternatives aligned with the user's interest.

YouChoose.ai

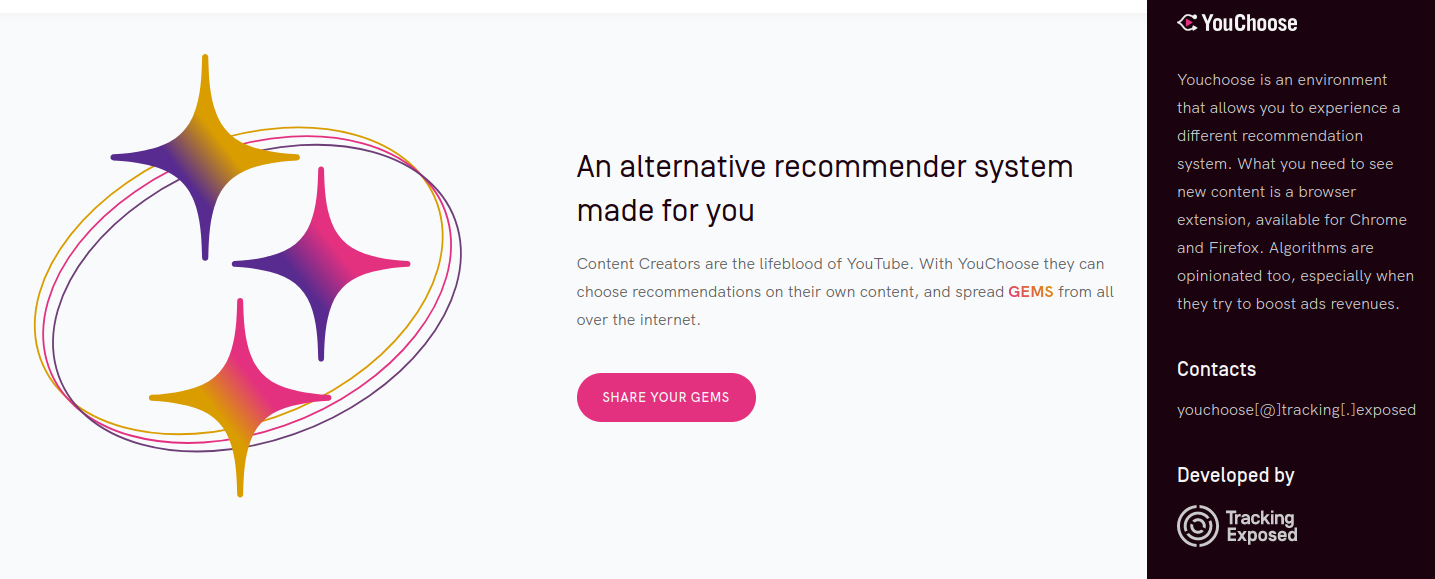

We developed YouChoose.ai, the first replacement for the YouTube content recommendation algorithm that was transparently governed by content creators rather than the opaque algorithms of YouTube.

This project was multifaceted and included a thoughtful and well-designed tool, the engagement of influencers, and the use of anonymous data donation to allow YouTubers to select which content was shown after their videos.

Our proof of concept also received praise from EFF’s Cory Doctorow, who understood our vision for adversarial interoperability. If the platforms won’t give us algorithmic agency then we are well within our right to take it: YouChoose allows you to change the way the YouTube algorithm works, on YouTube itself, without YouTube’s explicit permission.

YouChoose still holds a lot of promise for a scalable tool, but our core competency as a collective has been tech development and research, not product marketing. We came to realize the enormity of the task to help get YouChoose into the hands of users, and decided to keep the project as a proof of concept rather than an end user product.

Beyond the proof of concept, YouChoose is now being used as a tool for experimentation. In particular, a team of researchers from Berkeley and MIT are relying on it to investigate the impact of personalized recommendations on content consumption with several hundreds participants. The paper is expected to be written and published by the end of 2023.

We hope to develop YouChoose further in the future into a marketplace of algorithms for all of the world’s most popular platforms. If you’d like to fund this work as part of AI Forensics, please get in touch.

Step 5: Expose platforms through high profile press

After our brief tour into mass market product development, we returned to our pile of evidence of platform abuses and unaccountable influence on society, and started to think again about how to get people to really care and understand the harms we could see.

We decided to try pressuring platforms through public opinion and reaching regulators, policy makers and influential tech thought leaders via the international press. This required a more robust reporting format than typical academic publishing, and a bigger investment in communications.

Around the same time as this strategic decision, the war in Ukraine broke out. We felt compelled to investigate how TikTok - as one of the last platforms operating in Russia - was disseminating information to Russians.

With the guidance of strategic communications consultant Louise Doherty, our team produced 3 reports in 2022 that highlighted some serious issues with TikTok’s actions in Russia:

- TikTok blocks 95% of content for users in Russia

- Pro-war content dominates on TikTok in Russia after failure to implement its own policy

- Shadow-promotion: TikTok’s algorithmic recommendation of banned content in Russia

These reports were picked up in the Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, NPR, The Guardian, Le Monde and many other media outlets. Our continued scrutiny kept TikTok continually on the back foot over a 6 month period, and forced them to change or clarify their content policy each time. Our reports also sparked a letter to the US Senate and paved a piece of the path towards TikTok Congressional Hearings of 2023.

Following this success of this strategy, we continued to leverage different media channels to increase the reach of our research. Our report describing our monitoring of the French 2022 Elections was featured in a video from Forbes and the Center for Humane Tech's popular podcast Your Undivided Attention. Our results were also presented in a governmental election integrity committee led by the French media regulator ARCOM.

Our success with this investment in communications is a key learning that we take from Tracking Exposed into the new chapter of our work as AI Forensics.

What we learned

Over the seven years of work on algorithm accountability at Tracking Exposed we learned some extremely valuable lessons that I hope will be helpful to anyone considering entering this space.

-

The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house ~ Audre Lorde

We set out believing that there was a role for independent data collection and analysis of influential algorithms. Time and time again we proved that platforms do not have the right incentives to mark their own homework - and therefore cannot be trusted to dismantle the systems they have built that lead to the harmful influence of opaque, unaccountable algorithms in our lives. Even when the requirements for transparency increase and regulatory measures become stronger, platforms find a way to evade accountability. The role for activists and civil society to conduct independent scrutiny is as important as ever, despite growing awareness of the issues and well intentioned people inside and outside of powerful platforms.

-

Building is hard - do it together (please)

Building products is hard, building an organization is hard, building community is hard. It’s all hard. But it becomes easier when the work and the expertise is shared. We still believe that it is better for everyone in the field to collaborate to wield collective power in the face of near infinitely-resourced, monopolistic platforms - but we learned that not everyone in the field feels this way. Collaboration will remain a key part of AI Forensics.

-

Litigation is too slow

If we were concerned that regulation was too slow, litigation is even slower., and we have learned that it is better for specialized legal organizations to conduct such work. Though, we will continue to cheer those who are pursuing this theory of change, and we are happy to support them through AI Forensics with technical expertise and evidence collection.

-

High profile press scrutiny works

Conversely, we found that leveraging high profile, international press was the most effective way to drive impact. TikTok was forced into making tangible changes to its policies and platform behavior following reports of our work in the Washington Post and others, and our reports prompted 6 US Senators to write an official letter to TikTok's CEO summoning him to clarify and fix its policies, andt paved the way for congressional hearings of 2023. If we want our work to have impact, we must take the time to communicate it fully, and this requires investing in communication alongside our existing expertise in algorithm audits and building free software technology inside AI Forensics.

-

Focus and leverage expertise

When we started Tracking Exposed we knew the problems, but we didn’t know what the solutions were. We had to do a lot of experimentation before we found what works. This led to us doing research, building research tools, training researchers, contributing to policy, taking on litigation and building multiple tools and platforms for multiple audiences. Exploring lots of paths was key to discovering what works, but it also led to us pursuing too many things. To really scale our work we must focus on fewer projects, and leverage our unique gifts: research and technology. This is incredibly hard when there is still so much work to do in the field.

-

We have world class technology and team of expert algorithm auditors

For 7 years, Tracking Exposed has pioneered new tools and methodologies to scrutinize opaque platforms. Through these efforts, we have developed world class knowledge and a team of experts who can deploy their expertise into many fields of algorithmic accountability very quickly. We are proud that this expertise is independent from the platforms, independent from research institutes and independent from financial incentives that could sway us from our path. Under AI Forensics we plan to leverage our collective independent algorithmic audit expertise more fully.

In addition to these learnings, I want to highlight that Arikia Millikan led an outstanding effort in 2018 writing a 20 page document explaining the challenges, vision and goal of working in algorithm accountability.. She was the first trying to make a sense of how to have an impact in this field. If you want to start an algorithm accountability project please check it out - many concepts there are still valid in 2023.

The Changing Landscape of Algorithmic Accountability

As Tracking Exposed evolved into the non-profit AI Forensics, we carefully considered how the landscape has changed since 2016 in order to work out how we can best contribute to the field today.

-

We have more awareness

From Cambridge Analytica’s weaponizing of Facebook in the Brexit referendum to Elon Musk’s chaotic musings on the role of Twitter’s algorithm and content moderation policies on democracy, the public debate has moved from “algorithms are bad” to more nuanced debate like the difference between freedom of reach and freedom of speech. More and more people are coming to understand the opaque, unaccountable role of influential algorithms - not just experts and researchers. We are grappling with the geopolitical implications of this with TikTok, the first non-US social media company whose entire value proposition IS how well its algorithms know you. When we see protesters chanting “f**k the algorithm” we know the movement against algorithmic power is well on its way.

-

The algorithmic accountability field has expanded

Thanks to the hard work of many researchers, we now have multiple fields: workers’ rights (especially the gig-economy), content policy, personalization and platform politics among others. Researchers can specialize to really go deep on the issues and contextualize them in a way that wasn’t possible in 2016. This is one of the major reasons why the Tracking Exposed umbrella was becoming way too small for all the paths we were pursuing. Although all of these subdomains seem to belong to the algorithmic accountability field, algorithmic auditing is just one method to showcase the problem and it might not be impactful enough in each of these specific knowledge fields. For example, gig-economy means working closely with riders, with labor unions. It is something that I follow closely with the ETUI, and a forthcoming publication that connects platform reverse engineering with riders right is going to strengthen that research line even more, but a small team like ours couldn’t be effective with so much broadened scope.

-

Regulation is getting there

The growing awareness urged policymakers to act but they lack evidence and are not data-driven so there is a long way to go.. AI Index 2023 report’s analysis of the legislative records of 127 countries states that the number of bills containing “artificial intelligence” that were passed into law grew from just 1 in 2016 to 37 in 2022. In the EU, we now have multiple pieces of legislation to fight back against Big Tech’s algorithmic power that we didn’t have in 2016, including GDPR applied to training data, the Digital Services Act, Digital Markets Act, AI Act, Code of Practice in Disinformation, and the Directive on improving working conditions in platform work. The impact of these new regulations are still to be seen, and Big Tech’s lobbyists are still extremely powerful and policymakers and regulators have a huge task ahead of them.

-

Prosecutions are coming

Supported by the Digital Freedom Fund and Reset, we at Tracking Exposed handled two strategic litigation, one towards PornHub and the other on a gig-economy platform still not openly disclosed. It is too early to say what the impact of these will be on the ecosystem and on platform behavior, but these prosecutions are definitely coming. This was inconceivable in 2016, as now, the algorithm analysis methodologies are peer-reviewed and tested as evidence in court. According to the AI Index 2023 report, in 2022, there were 110 AI-related legal cases in United States state and federal courts, roughly seven times more than in 2016.

-

Civil society is stronger

A huge number of important and influential ecosystem actors have evolved alongside Tracking Exposed, many of whom are close collaborators, and friends. In particular, we see and appreciate the contributions of AlgorithmWatch, The Markup, AlgoCount, EDRi, ATI, Amnesty International’s Platform Accountability Lab, Mozilla Foundation, many of them now have their own data donation program. Also dedicated funders exist, such as the Digital Freedom Fund, European AI & Society Fund and more. We are together in this fight, and will remain close to the ecosystem as AI Forensics.

-

Alternative platforms increased uptake

We believe that decentralized technologies like the fediverse, and platforms, like Mastodon, are key to breaking down the monopolistic power of platforms. In 2016 Mastodon just began existing, now a whole new ecosystem of federated platforms is getting traction. We are also excited about the development of BlueSky, an interoperable protocol for social media recommender systems very much in the same philosophical vein as the proof of concept we built with YouChoose.ai. This still feels like a huge growth area for the field, and we are a long way from mass market solutions for all platforms - but the light is at the end of the tunnel. AI Forensics will not pursue these projects, but I personally am committed to interoperability and the fediverse, and will continue this work.

Conclusion

Ultimately, despite all the progress in the field, we still do not have control over the algorithms in our lives. If algorithms are inevitable, then what is a good algorithm that works in service to us?

We have come to believe that what we need are algorithms that are:

- Explainable

- Adjustable

- Accountable

- Avoidable

These principles behind what makes a good algorithm will form the foundation of our work at AI Forensics. We’re excited to share more about our stellar team, our theory of change, our areas of intervention and our plans for the future. If you’d like to be the first to hear more about the launch of AI Forensics you can sign up here.

A thousand thank yous!

I couldn’t have conceived of the support I would receive while building Tracking Exposed when I set out in 2016. Thank you to each and every one of you who contributed to our success, our learnings and ultimately helped to lay the foundation for our future as AI Forensics.

Thank you to our Contributors, divided in the three phases of this journey: the hacktivist experiment (2016-2018), ALEX the academic tool (2018-2021), and as last, the NGO path.

Alberto Granzotto

Renata Avila

Andrea Raimondi

Manuel D’Orso

Luca Corsato

Sanne Terlinger

Massimiliano Degli Uberti

Greg McMullen

Federico Sarchi

Eduardo Hegraves

Raffaele Angus

Costantino Carugno

Daniele Salvini

Giovanni Civardi

Arikia Millikan

Emanuele Calò

Michele Invernizzi

Stefania Milan

Jeroen der voss

Davide Beraldo

Salvatore Romano

Giulia Corona

Riccardo Coluccini

Marc Meillassoux

Laura Swietlicki

Aida Ponce

Leonardo Sanna

Matteo Renoldi

Giovanni Rossetti

Stefano Rossetti

Gaetano Priori

Barbara Gianessi

Marc Faddoul

Simone Robutti

Giulia Giorgi

Andrea Ascari

Alessandro Ghandini

Louise Doherty

Ilir Rama

François-Marie de Jouvencel

Margaux Vitre

Andrea Togni

Natalie Kerby

Miazia Schüler

Alessandro Polidoro

Alvaro de Frutos

Katya Viadziorchyk

Thank you to our Funders!

Mozilla, Reset, European Research Council through DATACTIVE, Web Foundation, #KeepItOn, Open Sensors Data, EU Horizon 2020 through NGI Ledger and NGI Atlantic, Digital Freedom Fund.

May 10th, 2023 – Claudio Agosti